On February 4th, 1861, The Provisional Confederate Congress convened in Montgomery, Alabama. During the following four days, the Confederate constitution was drafted and Jefferson Davis was nominated as president.

Representative Miles Taylor of Louisiana withdrew from the U.S. Congress on February 5, 1861. Fellow Louisiana Representative John Bouligny countered Taylor, declaring that he would not withdraw his seat. Bouligny proclaimed that he would "continue to be a Union man, and should stand under the flag of the country that gave [me] birth." He retired to private life and remained in the North during the war.

Union General Ulysses S. Grant captured Fort Henry, Tennessee on February 6, 1862. He captured Fort Donelson just ten days later. These two events helped him earn the nickname, "Unconditional Surrender" Grant.

During the Civil War, fast and rampant outbreaks of infectious diseases caused more casualties than battle related injuries. These diseases included typhoid, typhus, malaria, diarrhea, dysentery, measles, and smallpox. The Union Adjutant General's office recorded 5,825,480 admissions to the sick report in 1865. Diarrhea accounted for 1,400,000 of those cases, nearly 25% of the total.

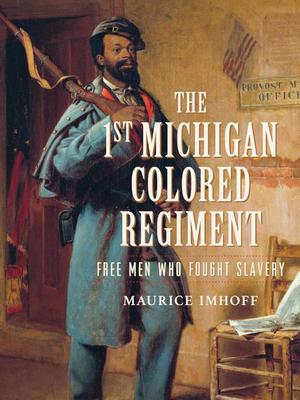

The Grand Rapids Civil War Round Table is proud to welcome a new speaker, Maurice Imhoff, and his presentation, "The 1st Michigan Colored Regiment (U.S. Colored Troop)." Following the Emancipation Proclamation, the U.S. military formed the United States Colored Troops. Even as black soldiers fought and died, their citizenship status remained uncertain. Racist policies limited opportunities for black soldiers to become line officers and paid them lower wages than whites. Join us as Maurice Imhoff covers the story of the 1st Michigan Colored Regiment, otherwise known as the 102nd United States Colored Troops, discussing its early authorization to present-time remembrance.

“Let the black man get upon his person the brass letters U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on the earth or under the earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship” – Frederick Douglass, April 6, 1863.

Maurice Imhoff is a dedicated Michigan historian specializing in the state’s African American Civil War regiment, with a strong commitment to preserving and sharing the histories of marginalized communities. In 2020, he co-founded the Jackson County Michigan Historical Society, where he actively promotes awareness and appreciation of local history. His passion for the field led him to earn an internship at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, making him the youngest person ever accepted into this prestigious program. There, he collaborated with curators from the Division of Cultural and Community Life and the Division of Political and Military History, gaining invaluable insight into historical preservation and public education. Maurice also serves as the executive program director of the Gospel Army Black History Group, the nation’s largest student living history organization, which is dedicated to telling the story of the 102nd United States Colored Troops. In just the past year and a half, the organization has achieved national impact and formal recognition, earning honors and commendations from the Governor of North Carolina, the Governor of Illinois, the Florida State Senate, the Mayor of New York City, Governor Gretchen Whitmer, the Michigan Legislature, and other respected institutions and award bodies. In addition to his work with these organizations, Maurice serves on local historical boards and is chairman of the City of Jackson Historic District Commission, reflecting his broader dedication to preserving Jackson’s cultural landmarks and fostering public engagement with local heritage. Through lectures, writing, and community-based projects, he continues to ensure that these vital stories are preserved and shared for future generations.

Membership fees for the 2025-2026 season are $30.00.

Checks can be made out to GRCWRT.

Get your membership/renewal form on our website

membership page or at one of our meetings.

Dues are based on the meeting year, September - June.

We are always looking for new speakers. If you would like to give a presentation to the GRCWRT, or can recommend someone, please contact our program director.

Wednesday

February 18, 2026

Maurice Imhoff

The 1st Michigan

Colored Regiment

(102nd U.S. Colored Troop)

We Meet At:

Orchard View Church of God

2777 Leffingwell Ave. NE

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Located at the southwest corner of

3 Mile Road NE and Leffingwell Avenue NE

Doors open at 6:30 p.m.

Program begins at 7:00 pm

Civil War Notes

Our Next Meeting

Special Announcements:

Maurice Imhoff's Book

The 1st Michigan Colored Regiment

Free Men who Fought Slavery